In a previous post, we analyzed this graph to understand the linguistic repertoire of our simultaneous bilinguals. Simultaneous bilinguals, who make up the majority of our emergent bilinguals nationwide, are those exposed to more than one language before reaching age 5. In the United States, we generally refer to simultaneous bilinguals as those who speak a Language Other Than English (LOTE) at home and are simultaneously exposed to English through another relative, daycare, television, etc. On the other hand, sequential bilinguals are those students who are exposed to only one language until age 5 and at some time after the age of 5, begin to learn another.

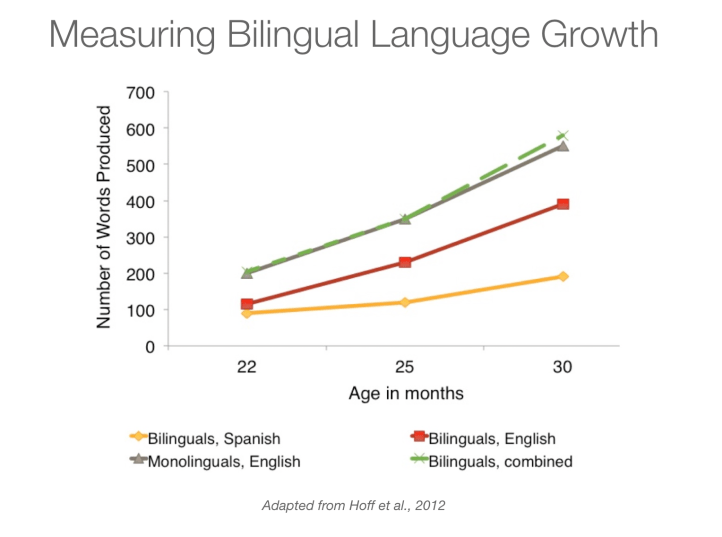

We used the graph above to note that toddlers who are exposed to both Spanish and English from birth tend to produce less words in each language than monolingual English speaking toddlers of the same age produce in English. However, by the time simultaneous bilingual toddlers are two years old, they produce more words in both languages combined than their monolingual, English-speaking counterparts produce in their one language. Hence, we should honor the fact that our simultaneous bilinguals actually have a larger linguistic repertoire than their monolingual counterparts although testing may show that they are “not proficient” in either language.

As great as this finding is and as much as it demonstrates the underlying asset of bilingualism, there is a shadow cast by this graph. Bilingual toddlers in the United States who are learning Spanish and English, although exposed to the Spanish at home, produce less words in Spanish than they do in English. By 22 months, they are already producing more words in English, and the gap between the number of words they produce in both languages only increases as they grow older.

There are many reasons we can postulate for any simultaneous bilingual toddler to produce more words in English than in Spanish. First, the child may spend more waking hours at daycare than at home. Additionally, at home, the child may be more exposed to English television and/or apps. But regardless of the reason, such a gap between languages sets children up to lose their Spanish as their proficiency growth in English outpaces their proficiency growth in Spanish, a phenomenon that is only likely to accelerate when students are in English-only programs versus Dual Language Bilingual Education (DLBE) programs. And considering that Spanish is the second most common language spoken in the United States, that gap is likely wider for children whose LOTE is a language other than Spanish.

Language endangerment at such a young age only serves to emphasize the need to find ways to help students grow in their home language. First, we have to increase the status of all LOTEs spoken at our schools. Bulletin boards with pins that represent languages spoken by students at the school is one strategy. I once worked at a school that had the word “welcome” painted in multiple languages on the wall. Making bulletin boards multilingual around the school can also help normalize the usage of different languages. But even more important than all of these strategies is to have periodic conversations with students about the importance of being multilingual.

As Director of Multilingual Education, I often went to classrooms and asked students to raise their hands if they spoke a LOTE and asked them to identify the language(s). I did my best to learn how to say `hello’ in the languages represented. Especially the younger students were overjoyed to hear their languages spoken at school even if it was just me saying, `hello.’ I went on to tell them that their multilingualism was their superpower and to encourage them to keep speaking their LOTEs. And I promised our younger monolingual, English-speaking students who were not in DLBE classes that the future held opportunities for them to learn a second language and encouraged their older counterparts to take their World Language classes seriously. For many of our emergent bilinguals, it was the first time that being multilingual gave them status in the classroom.

Next, we have to provide students opportunities to grow their language. DLBE classes are best for helping students become bilingual when there is a sufficient number of students at the school who have the partner language as a home language. For low incidence languages, heritage world language classes, often dependant upon virtual providers, can provide the support students need.

Finally, parents should be encouraged to help their students maintain the home language. Many parents mistakenly believe that their kids knowing multiple languages will slow their academic progress. This could not be further from the truth. The cognitive benefits of knowing multiple languages far outweigh any initial confusion that may accompany learning multiple languages.

At a time when nativism is running high, we have to be proactive about helping our students maintain or develop their multilingualism.